The French essayist and novelist Andre Gide once wrote, “Believe those who are seeking the truth; doubt those who find it.”

Scratch the surface of any thinking ideologue and you’ll find not certainties but contradictions and doubts.

Darwin’s doubts about natural selection and evolution

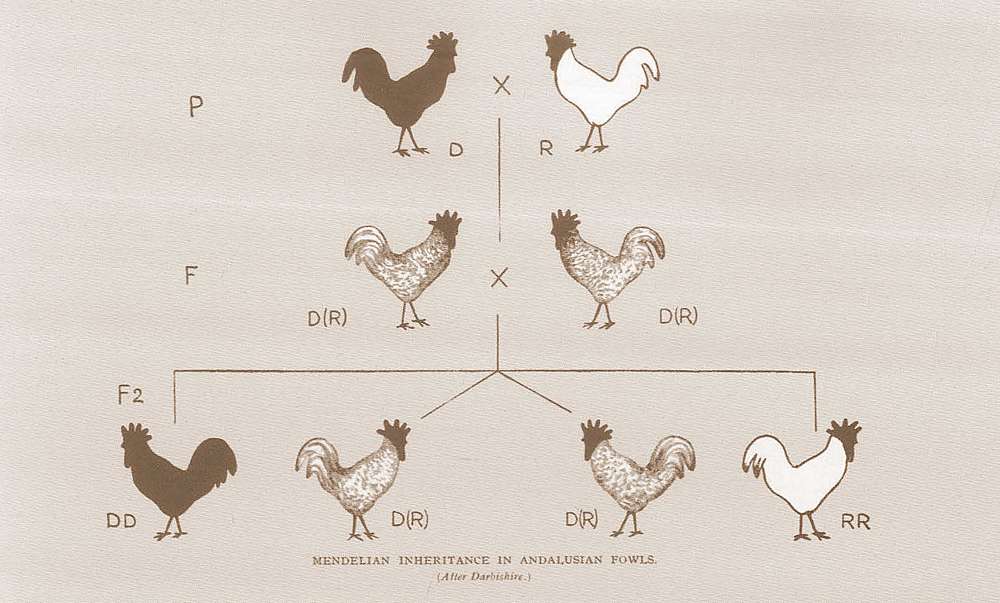

Even after the publication of his seminal Origin of Species and The Descent of Man, Charles Darwin had crippling doubts about some aspects of natural selection. Specifically, if natural selection was to have lasting effects, evolutionary advances had to be conserved and passed on from one generation to the next. Darwin agreed with scientists who argued that his evolutionary theory failed to explain how variations are transmitted from parents to their offspring.

It was not until the 1930s that biologists started to study Gregor Mendel’s work on genetic inheritance and heredity in conjunction with Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Only then did biologists come to understand how variation of characteristics is passed on to new generations and how evolution is a process of descent with modification.

Seek to have an idea tomorrow that contradicts your idea today

At a Q&A at American web application company Basecamp, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos opined that people who are “right a lot” are those who had a flexible mindset and often changed their minds. Summarizing the conversation, Basecamp co-founder Jason Fried wrote,

[Bezos] observed that the smartest people are constantly revising their understanding, reconsidering a problem they thought they’d already solved. They’re open to new points of view, new information, new ideas, contradictions, and challenges to their own way of thinking.

He doesn’t think consistency of thought is a particularly positive trait. It’s perfectly healthy—encouraged, even—to have an idea tomorrow that contradicted your idea today.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a well formed point of view, but it means you should consider your point of view as temporary.

What trait signified someone who was wrong a lot of the time? Someone obsessed with details that only support one point of view. If someone can’t climb out of the details, and see the bigger picture from multiple angles, they’re often wrong most of the time.

Idea for Impact: Wisdom comes from seeking wisdom

Want to learn, expand your worldview, and broaden your mindset? Start by seeking out the right people—mix with people other than those from your own background (professional, cultural, social, academic, racial, ethnic, etc.) Remember that birds of a feather do flock together. Instead of preferring the company of other people from similar backgrounds, try investing some time with people who have viewpoints that contrast your own.

French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre once wrote, “Seek those who find your road agreeable, your personality and mind stimulating, your philosophy acceptable, and your experiences helpful. Let those who do not, seek their own kind.” Look for those who respect your worldview—even if drastically different from theirs—but can present alternative perspectives and push you into considering different viewpoints on any issue of mutual interest.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Vincent embarked upon his artistic career at the somewhat advanced age of 27. According to

Vincent embarked upon his artistic career at the somewhat advanced age of 27. According to

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)