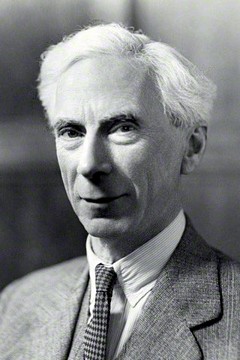

.jpg) Bertrand Russell’s 1912 book The Problems of Philosophy tackles fundamental questions that have occupied thinkers for centuries—profound, “cosmic” inquiries that blur the boundaries between philosophy and religion. Russell’s central argument is both simple and radical: philosophy isn’t merely an academic exercise but a vital necessity for human freedom and flourishing.

Bertrand Russell’s 1912 book The Problems of Philosophy tackles fundamental questions that have occupied thinkers for centuries—profound, “cosmic” inquiries that blur the boundaries between philosophy and religion. Russell’s central argument is both simple and radical: philosophy isn’t merely an academic exercise but a vital necessity for human freedom and flourishing.

Russell begins from an agnostic position, acknowledging that some questions about existence, meaning, and reality may never yield definitive answers. These inquiries delve into realms of subjective experience and values that neither science nor rationality can fully address. Yet he insists that “Human life would be impoverished if they were forgotten, or if definite answers were accepted without adequate evidence.” The value of philosophy lies not in providing answers but in keeping these questions alive and subjecting proposed solutions to rigorous scrutiny. This ongoing process of inquiry fosters a more thoughtful and meaningful existence.

While the reflexive comfort of dogmatic belief may provide temporary security, Russell argues it ultimately impoverishes the human spirit and threatens democracy itself. “Dogmatism is an enemy to peace, and an insuperable barrier to democracy,” he warns. He contends that even minimal philosophical education would help people see through the “bloodthirsty nonsense” propagated by dogmatic agendas. Philosophy serves as a safeguard against complacency and fanaticism, encouraging individuals to remain open to new possibilities and continually re-evaluate their beliefs.

Skepticism Over Sentiment: Philosophy As Conscience And Freedom’s Groundwork

Russell’s vision revives an ancient understanding of philosophy as a way of life. Drawing from Greek antiquity, he emphasizes that philosophy was never merely theoretical. Philosophers engaged deeply with the world, tackling real-world problems and advocating for social change.

“Socrates and Plato were shocked by the sophists because they had no religious aims,” Russell observes, noting that many ancient Greek philosophers “founded fraternities which had a certain resemblance to the monastic orders of later times.” These philosophical schools—such as those established by Pythagoras or Plato—formed close-knit communities with shared values, beliefs, and practices. The Pythagoreans, for instance, practiced vegetarianism based on their belief in the transmigration of souls, viewing the consumption of animals as akin to cannibalism.

“Socrates and Plato were shocked by the sophists because they had no religious aims,” Russell observes, noting that many ancient Greek philosophers “founded fraternities which had a certain resemblance to the monastic orders of later times.” These philosophical schools—such as those established by Pythagoras or Plato—formed close-knit communities with shared values, beliefs, and practices. The Pythagoreans, for instance, practiced vegetarianism based on their belief in the transmigration of souls, viewing the consumption of animals as akin to cannibalism.

In ancient Greece, traditional polytheism coexisted with an emerging intellectual tradition that sought rational explanations for the world. Plato’s Republic exemplifies this philosophical turn: Socrates argues that truth and goodness are inseparable—genuine knowledge requires moral integrity. The philosopher’s quest demands a complete reorientation of the soul toward goodness, alongside theoretical understanding of what the soul is and what benefits it. This perspective carried spiritual undertones; moral development enabled intellectual development, and the pursuit of ultimate knowledge took on a spiritual dimension. Cultivating virtues makes individuals more receptive to truth and less susceptible to falsehood.

Aristotle expanded these ideas through virtue ethics, arguing that character should be shaped to align with human flourishing. The ultimate goal of life is eudaimonia—often translated as “flourishing” or “living well”—a concept extending beyond mere pleasure to encompass purpose, meaning, and fulfillment.

The Value of Keeping Inquiries Alive Rather Than Settling for Easy “Consolations”

Russell aligns himself firmly with this tradition, insisting that “if philosophy is to play a serious part in the lives of men who are not specialists, it must not cease to advocate some way of life.” Philosophy equips people with tools to analyze arguments, identify biases, and make informed decisions about how to live.

Yet Russell sharply distinguishes philosophical from religious approaches to the good life. Philosophy rejects reliance on tradition or sacred texts, and he argues that philosophers should never attempt to establish a church. He viewed authoritarianism as central to religion, and on that basis, his philosophy is staunchly anti-religious. His perspective centers on ethical skepticism—philosophy subjects all purported answers to rigorous examination. For Russell, philosophy should lead to peace: both inner tranquility and social harmony. By refusing to settle for easy answers, it prevents intellectual stagnation and protects society from fanaticism.

At its heart, Russell’s insistence isn’t a matter of abstract speculation but of lived necessity. Philosophy, he reminds us, is the groundwork of freedom and the soil in which human flourishing takes root. It will never rival science in its certainties nor religion in its consolations, but perhaps that’s its gift—an invitation not to be comforted but to be liberated. To live well isn’t to cling to dogma but to cultivate the ongoing discipline of asking, of doubting, of seeing more clearly. In this, philosophy becomes less a subject of study than a practice of conscience, a way of being that binds our private integrity to our shared responsibility.

Minor annoyances can drain you more than you realize. They don’t vanish after the moment passes; they linger, filling every bit of mental space you allow them. The irritation itself is brief, but the

Minor annoyances can drain you more than you realize. They don’t vanish after the moment passes; they linger, filling every bit of mental space you allow them. The irritation itself is brief, but the

In

In  Few things feel more exhausting than the annual tradition of drafting New Year’s

Few things feel more exhausting than the annual tradition of drafting New Year’s  Modern life tempts us toward simple ideals—peace, joy, freedom—but wisdom lies in reimagining these not as escapes from discomfort, but as quiet, sustained negotiations with the

Modern life tempts us toward simple ideals—peace, joy, freedom—but wisdom lies in reimagining these not as escapes from discomfort, but as quiet, sustained negotiations with the  Optimism’s useful—good for your mind, body, and well-being. But it’s not a cure-all.

Optimism’s useful—good for your mind, body, and well-being. But it’s not a cure-all. November 20 is

November 20 is  It’s a curious feature of our age that we still require, by law, ashtrays in the lavatories of commercial aircraft. Not because we’re nostalgic for the days when the skies were thick with the fug of unfiltered Marlboros, but because—despite decades of prohibition—someone, somewhere, will inevitably decide the rules

It’s a curious feature of our age that we still require, by law, ashtrays in the lavatories of commercial aircraft. Not because we’re nostalgic for the days when the skies were thick with the fug of unfiltered Marlboros, but because—despite decades of prohibition—someone, somewhere, will inevitably decide the rules .jpg)