There’s an old joke about the Soviet Union’s approach to industrial planning. It’s been told so often it’s practically folklore, but like all good parables, it endures because it captures something fundamentally true about human behavior under pressure.

There’s an old joke about the Soviet Union’s approach to industrial planning. It’s been told so often it’s practically folklore, but like all good parables, it endures because it captures something fundamentally true about human behavior under pressure.

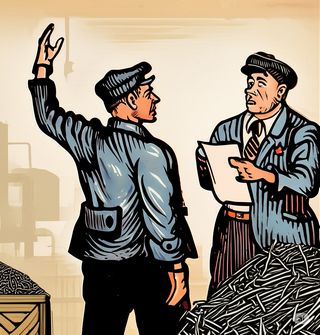

In the days of the Soviet Union, Moscow set production quotas, which became the dominant concern of factory managers.

When a commissar told a nail factory’s manager that he would be judged on the number of nails the factory produced, the factory had made lots of little, useless nails.

The commissar, recognizing his mistake, then informed that the factory manager’s performance would be judged on the weight of the nails produced. Consequently, the factory then produced only big nails.

This isn’t just a cautionary tale about bureaucratic absurdities. It’s a lesson in what happens when incentives are designed by people who assume that metrics are neutral, incorruptible things. They’re not. Metrics are like mirrors in a funhouse: they reflect something, but rarely what you intended.

Myles J. Kelleher, in Social Problems in a Free Society: Myths, Absurdities, and Realities (2004,) offers another gem from the Soviet archives:

One Soviet shoe factory manufactured 100,000 pairs of shoes for young boys instead of more useful men’s shoes in a range of sizes because doing so allowed them to make more shoes from the allotted leather and receive a performance bonus.

The logic is impeccable. The outcome is ridiculous. And yet, this isn’t just a Soviet problem. It’s a human one. People respond to the rules of the game. If you reward volume, you’ll get volume—regardless of whether it’s useful, desirable, or even remotely sane.

The significance is blunt: people don’t optimize for purpose; they optimize for score. And if the scoreboard is flawed, so is the game.

Idea for Impact: Don’t Incentivize the Wrong Game

The moment you tie rewards to a number, behavior shifts to serve that number—regardless of whether it reflects anything meaningful. That’s the risk. What gets measured gets done, but it also gets distorted or quietly avoided. The point is to measure what matters, and to understand why it matters.

Start by asking what you’re trying to achieve. If the goal is customer satisfaction, measure the experience, not the volume of calls. If it’s innovation, don’t count patents—look at whether they solve real problems. Activity isn’t the same as effectiveness, and often works against it.

Then look at the resources involved. Efficiency only matters if it supports a valuable outcome. A team chasing empty metrics isn’t efficient—it’s drained. And before introducing any performance measure, ask how it might be exploited. If someone can meet the target while ignoring the purpose, you haven’t built accountability—you’ve created a loophole.

Metrics are instruments. Used well, they clarify. Used poorly, they mislead. Measure carefully.

Reward carelessly, and you’ll get exactly what you asked for—just not what you needed.

Leave a Reply